Thursday, December 31, 2009

Mitumba

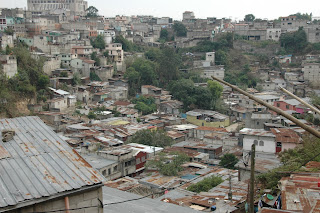

Mitumba is a tiny little slum, a mere 15,000 people jumbled together in a tiny corner of the city. Airplanes from Wilson airport zoom overhead and across the fence is the edge of the Nairobi Game Park.

Mitumba is a Swahili word for "cast off," or "second-hand," or "worthless." It's the name Kenyans give to the huge loads of cast-off clothing that makes its way here from North America. It's Mitumba, cast-off, no one else wants it. Mitumba is where these people live.

It's also a state of mind. Pastor Shadrack knows full well that these people consider themselves "Mitumba." Of no worth. Cast off.

Shadrack and his wife, Violet, have been at work here since 2002 and their number one goal is to move this mindset from "worthless" to "of great worth."

They're doing an excellent job.

They and a crew of volunteers and staff educate over 400 children grades one through eight, and feed them too. They shelter over 20 orphans; kids who have lost both parents. They preach the Gospel and a lot of other things too.

To an outsider, the ramshakle buildings where this all takes place, tucked in Mitumba Slum, are nothing special. In fact, they don't look so much different from the other shacks and buildings going on. But the fact is, these buildings--and what happens inside them--is absolutely transformative.

Over the years, not only has education increased, but so has hygiene, and trust. Two years ago, when slum communitities around Kenya were erupting with violence because of the presidential elections, only Mitumba Slum was spared the violence. Shadrack and Violet were later recognized by the government for this rather impressive feat.

But more importantly, the people of Mitumba are beginning to realize that this name--Mitumba--does not have to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. It's just a name, and they do have worth. They're starting to know that now.

So for the next week, Daniel, Luke, Hani and Danielle will have the awesome privilege of trying to tell this story in a compelling way. It's one of the pro bono projects we're doing to do our bit to help those who are helping the poor.

Oh, Andrew showed up this morning so we're all here. Excellent.

Feels Like Home

It feels great to be back in Kenya, where I lived for 7 years. And it's great to share the experience with a dozen other people. In the days ahead, we're looking forward to meeting some great people, telling stories and using cameras and mics to help others understand the stories we want to tell.

Talk to you soon.

Saturday, December 12, 2009

Into Africa

orking closely with Pastor Shadrack Ogembo, Pastor Daniel Ogutu, and a new friend, Father Ted Hochstatter.

orking closely with Pastor Shadrack Ogembo, Pastor Daniel Ogutu, and a new friend, Father Ted Hochstatter.  Pastor Daniel is my main contact for finding just the right family for the documentary. He has already sent me some pictures--the ones you see in this blog--of people he feels will help us capture the story of the one billion people living in slums.

Pastor Daniel is my main contact for finding just the right family for the documentary. He has already sent me some pictures--the ones you see in this blog--of people he feels will help us capture the story of the one billion people living in slums.

Please keep an eye on this space over the next few weeks as I'll be putting stories here of what we discover, who we discover, and what we learn about what I'm starting to refer to as "The Fourth World," the world of slums.

Please keep an eye on this space over the next few weeks as I'll be putting stories here of what we discover, who we discover, and what we learn about what I'm starting to refer to as "The Fourth World," the world of slums. Sunday, June 21, 2009

LONG-Term Disaster

The other night, GenAssist threw a huge party at one of the universities here in Aceh. 500 or so people showed up, the governor of the region, the mayor, other important government o

When disasters hit an area, they tend to hit the news headlines pretty hard too. We probably all remember the Tsunmai, the massive earthquake in China, the chemical explosion in India some years ago, Chernobyl. But once the headlines fade away, so do our thoughts of the event.

This celebration was a powerful reminder that tragedies linger. For years. For the people of Aceh, the Tsunami will not be a distant memory for the next few generations. You can’t drive very far through this city without seeing a monument, a plaque, an escape building, a mass grave, and be reminded that this Tsunami was for the people of Aceh what Hiroshima/Nagasaki was for the Japanese a few generations ago. It forever changed them.

Seeing that celebration also made me realize that organizations that go in, claim the limelight while it’s there, then leave, would be better off never showing up in the first place. It’s quite possible that they do more harm than good.

CRWRC goes in for the long haul. They stick it out until the job is done, or at least until the infrastructure and talent is in place to keep things moving toward restoration.

Here in Aceh, they’ve built houses, trained thousands of people to have new livelihoods, worked with government leaders, and are leaving a very qualified and gifted group of people behind to tie up any loose ends in the months and years to come.

So even though the headlines left years ago, and our memories faded fast on the devastation of this Tsunami, my little blog is one attempt to bring to light the fact that this tragedy isn’t over yet. For the people of Aceh, it’s a daily reality. For CRWRC, it’s now a job well done.

As a footnote, CRWRC has just applied for a large grant to help them get started in Southern Sudan where a tsunami of war, violence, starvation and, dare we say it? Genocide? is under way. It will be interesting to see how long they stay there after the headlines fade away.

I suspect they’ll be there awhile.

Friday, June 19, 2009

The Photograph

We interviewed several people today and asked them to tell their story of what happened on Decemember 26, 2004, the day of the great Tsunami.

We interviewed several people today and asked them to tell their story of what happened on Decemember 26, 2004, the day of the great Tsunami. Ihya’s story goes like this:

He lived near the ocean and heard of what was coming. He grabbed their young son in one arm, and his wife was hanging onto the other arm. They ran—literally ran—for their lives away from the ocean.

As they ran, he looked back and “saw a mountain of water behind us.” They kept running, looked back again and saw the mountain coming closer.

His son was ripped from his arms, then his wife. He went unconscious and when he came too, saw he was near a roof a building. He grabbed hold but then that building collapsed.

Somehow he managed to survive.

Just before the Tsunami hit, Ihya’s parents made the pilgrimage to Mecca. Before they left, they took a picture of their son, his wife, and their son. That picture was in the camera they took with them to Saudi Arabia. It’s one of the only things Ihya has left to remember his family by. He had the photo enlarged and brought it out to show to us.

CRWRC, the organization that has worked here for the past four years, has helped Ihya, and hundreds and hundreds more just like him, aquire housing and meaningful work since the Tsunami. Seeing Ihya in his new home, and hearing him talk of the girl he’s now dating and hopes to marry, makes me realize that hope can emerge from such a dark story.

Thursday, June 18, 2009

Religion

, black domes. They are beautiful to look at and there’s something haunting about the call to prayer.

, black domes. They are beautiful to look at and there’s something haunting about the call to prayer. Our guide and driver, Yassir, is a Muslim. Today when we finally broke for lunch, we were just sitting down when he asked to be excused for “about 10 minutes.” It was time for prayer. That’s devotion.

Garuda Airlines, one of Indonesia’s airline companies, has an in-flight magazine. The current issue has two full pages, prominently displaced just before the maps in the back of the magazine, giving “Invocations” to all so we can pray before the flight takes off. These invocations are offered in a variety of languages, but I’ll just give you the English, exactly as printed in the Garuda magazine:

Islam:

We seek the help of Allah, the most Gracious, the Most Merciful… Who has bestowed upon us the will and ability to use this aircraft without Whom we are helpless. Verily, to God alone, we worship and to God alone we shall return. Oh Allah, shower us with Your blessings and protect us on this journey from any hardship or danger and protect also out family and our wealth.

Protestant:

Lord in heaven, we praise and thanks of thy bless and endless love in our live. In this opportunity, we call They holly nname to accompany our journey. We believe Thou will guard and protect our plane from any disturbance and danger. To the all air crew, Thou will lead their duty in order for us to arrive in destination in time and save. Thank you for Thy help and firm love from beginning, now, and forever, In the name of Yesu Christ, we pray, Amen.

Catholic:

In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, Amen. Long Ago You save the children of Israel who crossed the sea with dry feet. And three wise kings from the East received Your command with the guidance of a star. We beg You. Bless us with a safe trip, with good weather. Bless us with the guidance from your angels, so that the crew of this aircraft will lead us to our destination safely. We also hope that our family remain happy and peaceful until we land safely. Blessed be Your name, now and forever. Amen. In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, Amen.

Hinduism:

Om Sanghyang Widhi Wasa the Greatest, all wealth and intelligence comes from your blessings. Keep our minds and manners pure and let us attain inner peace and happiness.

Buddhism:

Praise be to Sang Bhagavca, the Pure. One who has attained enlightment (3x)

Let All Creature live in happiness in accordeance to Your will. (Paritta Suci).

Confucian

In The Name of TIAN, The God Almighty. In The Highest Place. Under the guidance of our Prophet Kong Zi. Be Honor. SHANG DI, The Supreme God. Please be your guidance for all the airline crews. So they can perform their job accordingly. Please bless us all. So that we can arrive at our destination savely. And so to unite with our beloved family.

Thursday, June 4, 2009

Rebuilding Banda Aceh

On December 26, 2006, a tsunami raced through the Bay of Bengal and killed over 260,000 people. Many of those victims were on the northern tip of the Island of Sumatra in Indonesia.

Since then, CRWRC (Christian Reformed World Relief Committee) has spent millions of dollars to put lives and communities back together. That’s not so unusual. CRWRC does that. What’s rather unique about this story is that Banda Aceh (pronounced A-chay), the community at the tip of Sumatra—the one that got hit hardest by the tsunami—is a Muslim community.

Next week I’m going to Banda Aceh to help CRWRC tell the story of what they’ve been doing since the tsunami hit.

It’s not part of the slum documentary, but yet it is. It’s a story about people who are “down on their luck,” people who needed a hand—and got one. Slum dwellers often don’t get that helping hand. Because their needs are chronic and never ending, we tend not to notice. But when a tsunami hits and takes out a couple hundred thousand people, we notice.

I’ll write about my experiences on these pages and tell some of the stories of the people I meet. I hope you’ll forgive me for using the Slum Doc blog to tell a different kind of story here.

On another note: I love fine coffee. My favorite is Sumatra from Starbucks. I’ll see what I can find on Sumatra J

Friday, May 22, 2009

Impunity

In Guatemala, that’s not so unusual. Last year, 620 women were murdered, and not one person was brought to justice over it.

While filming in Guatemala, we are staying at a seminary, the largest in Latin America. It’s a beautiful oasis in a violent city. High walls

surround lovely green areas, well-manicured lawns, well-kept buildings and engaging students.

surround lovely green areas, well-manicured lawns, well-kept buildings and engaging students. We left the compound at 8 a.m. for our day of shooting. At 7:30 a.m., the woman who cleans the rooms, makes sure the towels are fresh and who keeps the guest comfortable, was dropped off right in front of the main gate of the seminary.

A student who lives across the street was an eye witness to what happened next.

The cleaning woman (who’s name I do not know) alighted from the vehicle and moved toward the gate.

A car sped around the corner and a well-trained assassin leaned out the window with his pistol and shot the woman in the head.

The eye witness said it was a well-executed operation by a well-trained person. Apparently it’s quite easy to hire such a person in Guatemala.

One of the seminary professors knew the woman quite well and she’s the one who told us about the 620 murders of the previous year. Trembling with anger and frustration, the professor told us that most likely, some routine paper work would be done on this murder and then it would be put in a file somewhere and would most likely never see the light of day again.

Seeing her anger and helpless frustration gave me an inkling of what the residents of La Limonada slum must feel at times. The Ministry of Justice building is an imposing structure (see photo) that stands literally on top of the ridge

overlooking La Limonada. The task of the Ministry of Justice would be similar to the FBI in the USA. They are charged with investigating murders, suspicious deaths, etc. Being so close to La Limonada, a violent slum in a violent city, should be job security for them.

overlooking La Limonada. The task of the Ministry of Justice would be similar to the FBI in the USA. They are charged with investigating murders, suspicious deaths, etc. Being so close to La Limonada, a violent slum in a violent city, should be job security for them.However, as we found out, what happens in La Limonada stays in La Limonada. According to those who live and work down in that deep ravine, murders that happen there are just not worth investigating by the Ministry of Justice.

At certain times of the day, the shadow of the Ministry building literally falls into the slum. But that’s about all the residents of the slum will get. Murders down there are not investigated.

Imagine being one of those residents and knowing that murderers can operate with impunity. Simply being a resident of La Limonada makes you unworthy of official protection. You’re on your own.

The United Nations says some characteristics of slums include lack of security of tenure, lack of security and lack of sanitation. For those in La Limonada, we could also add lack of rights.

Selma's War

Imagine Job. You know, the guy in the Old Testament book of Job. Now add rape, sexual abuse, physical abuse and a severe beating with a machete, add a life-time of rejection by an alcoholic mother, being sold by her to the sex trade, a string of men who added to the rejection and abuse she felt, and you start to get an idea of what Selma’s story is all about.

Being a journalist, or in my case, a documentary film maker, opens up portals into stories and lives one could never enter otherwise. I remember interviewing a lovely woman in Sierra Leone who was finally, a few years after the war there, recovering her sanity. She was buried in a deep hole for days, was raped, assaulted, tortured, and made to hold the severed head of her aunt for hours on end. That happened during a war so in some bizarre, strange way, maybe the fact of war somehow lessens the horror of her experience for those that hear her story later.

But Selma’s story takes place in Guatemala. Today. The war officially ended in 1996 but even so, her story really had nothing to do with the “official” Guatemalan war.

When Selma finished telling her story to Tita and, in effect, to you the reader of this blog and eventual watcher of the film, Tita and Selma hugged each other tightly and they both wept for several minutes. It was a most holy moment there in Selma’s house. Iron sheets on a narrow spit of land on the side of the steep ravine that is La Limonada.

After catching my breath, Tita told me that Selma’s story is actually not that unusual. Women in Guatemala are abused and beaten all the time. “At least 50% of them,” she said.

I suppose poverty is a war of sorts. It assaults its victims and puts them in situations and predicaments that would seem unimaginable in peacetime. Selma, the men that beat her, the impoverished alcoholic mother, the men that used Selma when she was sold as a nine-year-old girl; all part of the violence of poverty.

Does it really have to be this way? In a world that generates so much wealth, does Tanya have to beg on that corner every day, and does Selma have to suffer so much?

Today, as I write this blog entry, Selma is experiencing yet another chapter in her life. She’s having surgery somewhere in Guatemala City to try and remove her cancer.

For her, the war goes on.

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

Begging from a Wheelchair

s a beautiful face and bright eyes that manage to laugh despite the physical and emotional pain.

s a beautiful face and bright eyes that manage to laugh despite the physical and emotional pain.Jesse and I followed with our Panasonic HVX hi-def cameras and we had Aaron with us, a friend we met last night. We gave Aaron the Nikon and let him go to work getting photographs for the website and future print pieces. Papa wheeled Tanya through the very narrow corridor on which they live. That empties out onto a wider alleyway. He took that down to the river and then followed the main road out of La Limonada. The main road goes up. It’s the only way to go. Papa doesn’t work as a painter anymore because he has such a sore hip. Picture him pushing Tanya in her wheelchair up a very, very steep hill. (Papa was so exhausted at one point that the film crew jumped in and pushed Tanya the rest of the way up the hill.)

Once at the top, traffic is the main enemy. Cars and trucks and buses fly by. Diesel fumes and smoke hang thick in the air. Papa and Tanya quickly and deftly maneuver through it. They do this every day and are quite good at it. The streets are level for several blocks, then go up again. The traffic in

So the work day began. She joked around and laughed with the flower vendor on the corner. They must see each other each day there on the corner. And she wheeled herself up and down that incredibly busy intersection in her low, blue chair, reachi

We shot this scene from a variety of angles. Sometimes when you see life unfold through a lens, rather than just watching it with the naked eye as you pass by, you see things differently. What I saw was how incredibly vulnerable Tanya is. That tiny chair, with Tanya in it, next to rumbling buses, diesel trucks, expensive cars and beat-up junkers. Some reach their hands out and place some coins—or paper bills—in the cup. Others ignore her. Others literally don’t see her. This is her life. She does this each and every day because she has to to survive.

By seeing the behind-the-scenes story of this one beggar on a street corner, I and my team have had our perspective changed of beggars in general. It the future, It will be mighty hard to see someone working a street corner in the Developing World and not immediately think of Tanya. We’ll wonder what the story is, who the Papa is, how much do they need to survive, what kind of room do they sleep in.

Getting to know one person has made me aware of a whole class of people.

That’s what this documentary is about. Maybe if viewers get to know a few slum dwellers, li

All one billion of them.

(photos for this posting: thanks to Aaron Kreuger.)

Monday, May 18, 2009

Behind the Black Door.

If you wind your way up from the sewage through narrow alleys, you’ll come to another alley, more narrow yet, and one of thousands just like it. Turn right, wend your way through it and pound on a black door. A man will open the door and let you in. We stepped through a tiny courtyard—literally about six feet across—and into Tanya’s bedroom.

She was laying on her bed, covered with a blanket. The first thing we noticed is that the “normal” shape of a person under a blanket was missing. And that’s part of Tanya’s story.

I won’t trouble you with all the details, we’ll cover more of that in the documentary, but here’s the short version. Membership in a gang, brothers murdered, Tanya shot, bullet hits her spinal cord, she loses the use of her legs, later a severe break means she has one of the legs amputated, she now lives in this tiny room with her father in his own room right behind her. She wheels herself to a busy intersection each day and works—rain or shine—begging next to the cars when they stop at the traffic light. She must earn about 50 Quetzales each day ($1=8Qs) to survive so even during rainy season—now—she must be out there begging.

At the end of a long day, she wheels herself back down into La Limonada, through narrow alleys to her own, comes to the black door and papa lets her in, helps her into bed so tomorrow she can do it again.

Tanya welcomed our crew into our home. She was painfully honest about her life, her frequent thoughts of suicide and her oft-repeated questions of “why me?” What troubles her greatly is the comments people make to her, or about her, as she begs at the corner. Rich people, particularly, are harsh, she says. She cried while telling that story.

She was also honest about how she gets through it all. Her faith in Jesus is what sustains her. By her

Tita is the woman who linked us up with Tanya … and is largely responsible for helping Tanya, and many, many more like her, find that deep and abiding faith. Tita’s story is a documentary in itself. Maybe another day.

Meanwhile, Tanya is resting behind the Black Door while I write my blog. Tomorrow morning we will be at the red door at 6:00 a.m. so our cameras can follow her as she makes her way out of La Limonada, over the crest, down to the busy stoplight and begin another day of survival.

Flowers in the Slum

The news finally reached the Drudge Report today, which means it’s pretty big.

Being here in Guatemala puts it all front and center.

There were demonstrations again in the central plaza today. We were there later and it looked like a hurricane swept through the plaza and left tons of garbage behind. We didn’t get there in time to film the event though because we didn’t come here to capture up-to-the-minute breaking news. We came to get the much older story of poverty.

Today was our first day of shooting in Guatemala. Joel A, our guide, drives us to the right places, tells us when to shut the windows of our car because the neighborhood is bad, translates for us, and gives us good advice and answers to our many questions.

We didn’t actually go into the slums today, that’s our job for the rest of the week. Today was a day to get the lie of the land, get some establishing shots, get some of the stuff we’ll forget about later like government buildings, landmarks, candid people shots, culture, sort of essence-of-Guatemalan-life shots.

We did get to the outskirts of La Limonada though. We went up on a precipice that overlooks the slum. Actually, the slum creeps right up to the edge of that precipice and almost crawls over. We shot long, wide establishing shots to show this piece of the slum when we were quietly and wonderfully interrupted by the type of hospitality poor people are so good at.

We were shooting when Joel started talking with a tiny, elderly Guatemalan woman who’s home almost reached the top of the precipice. She was curious. What were we doing? He explained. She invited us—four strangers from another country, plus Joel—into her house.

We might enjoy getting some shots through her window, she explained. Then she led us through her little house to the back onto a tiny verandah that emptied out onto more little homes straight down, down the slope of the embankment we were on, a perfect picture of how the very poor build their homes on the absolute worst and most dangerous pieces of land.

She had flowers on her verandah and proudly showed them to us. I asked her (through sign language. My Spanish is horrible) if I could take a picture of her with the flowers. She agreed. You can see her picture here.

We got some great footage from that vantage point; shots we would not have gotten without that serendipitous moment provided by that gracious Guatemalan woman.

In her home, I forgot all about the storm brewing in Guatemalan politics. I forgot completely that I was on the cusp of a slum and surrounded by poverty. In her home we were treated as friends. And our political persuasions, incomes and countries of origin didn’t seem to matter.

Thursday, May 14, 2009

From Tulip Lanes to Slums

It’s Tulip Time in my home town. It’s an annual celebration of all things Dutch. There’s Dutch Dancing in the streets, gorgeous tulips planted by the thousands all over town; there’s windmills and a canal, wooden shoes klomping all over the place and tourists by the thousands who bus in to see the street scrubbing, eat Dutch treats (including almond bars), watch the parades, take trolley tours and more.

In two days, four of us will be in La Limonda, Guatemala City, Guatemala. Though I haven’t ever been to this particular slum, I rather doubt we will see scrubbed streets, tulips, or even authentic ethnic costumes.

I suspect we will find many kind people who are generous to four strangers, and who are fabulously rich in community.

As I explained to my daughter Lauren once when we were filming in San Salvador; there are different kinds of riches. What she experienced there in that poor community was the richness of community. People knew each other, knew each other’s business, names, took the time to talk to one another. There wasn’t a lot of material wealth, but my young daughter definitely picked up on this other form of richness.

We were living in another state at that time, and we certainly did not have that richness of community. When we got back, she was hungry for it. She missed it.

Of the four of us, two of us, Jess and myself, have spent considerable time in this region of the world. Jess is a recent college graduate with a degree in digital media production. He grew up in the Dominican Republic and speaks Spanish fluently.

The other two will have their first taste of both Latin American culture and of slums. One is John, a friend of mine from town. He’s eager to see for himself what life in the slums is all about. John has a big heart for the poor and for justice. I’m eager to see his response.

The other traveler is my dad. He’s 70 years old and though he’s followed his kids around to East Africa and Israel, this week in La Limonda will be an eye opener for him. He’ll carry equipment, hold shotgun mics, recharge batteries and generally do whatever needs doing. And like the rest of us, he’ll meet people who are part of the one billion.

And he'll wonder how some of us can live in tulip-lined lanes, while others live in slums.

Tuesday, May 5, 2009

La Limonada, Guatemala: The Precarious Life

Why there and not a favela in Rio, or on the outskirts of Mexico City? Why do the Latin America shoot in Guatemala?

As we looked at the various slums in Latin America (unfortunately, there were plenty to choose from) we decided to focus on a slum that hasn't received much attention from the world. Not that most slums have, but some are more famous than others. Rio, for example, has been featured in several movies and the favelas are almost romanticised in some quarters. Funny how media can make a location famous (i.e., just think about the baseball fields here in my home state of Iowa.)

Guatemala is a small country right next to Yucatan, Mexico. We don't hear much about it in the news, it gets very little attention, and yet, 70% of the population lives on less than US$2 per day. In the countryside, 30% live on less than $1 per day. In the city, 8% does.

Guatemala City has about 2.5 million people and estimates show that at least 60% of them are poor. Those with the lowest incomes live in very precarious situations.

Our goal is to spend a week with two women who live these precarious lives; Tanya and Selma.

Tanya and Selma have stories that border on the unbelievable. We hope to make their stories real and believeable with our lenses and microphones. They live in a slum community called La Limonada, which had its beginnings in 1959.

When the government put an end to the agrarian reform program in the '50s, that, plus socio-economic problems accelerated the migratory process from rural to urban. About 600 families invaded the sides of the gullies in front of the Olympic Stadium and thus was born La Limondada, one of the largest slums in Central America today.

We don't know Tanya and Selma's history or complete story yet, but we hope to find out. As the author Chaim Potok said, "in the particular is contained the universal." Through the particular stories of Tanya and Sara, we may gain clear insight into the more universal story of the plights of tens of thousands more who live the precarious life in Guatamala City and in cities around the world.

I'll post more here about Tanya and Selma, the good people who are making this possible in Guatemala City, our experiences as we shoot, and what we learn. Thanks for checking in.

Tuesday, April 28, 2009

...better late than never.

Filmmakers get pretty excited about their films. That's good because it takes a lot of passion and energy to make one! They do the preproduction, they do the shooting, they do the postproduction, and then … then they start asking questions like, “Who's going to buy this thing?” “How will I get this out to my audience?”

I was very fortunate to come across Stacey Parks and her company, Film Specific. Stacey has a long history of working with independent filmmakers and getting sales and distribution deals put together for them.

Stacey had a nine-week, weekly conference call that about 50 of us from around the US and Canada were part of and the topic was, “Distribution in Reverse.” The premise being; whatever stage of production you're in right now, you need to be thinking clearly about the the final stage, which is, marketing and distribution.

To that end, our conference calls were useful in getting us to think about questions like international financing deals, global distribution, the film festival circuit, and the mother of all deal breakers: deliverables.

Deliverables are the myriad nit-picky little things that any TV distribution deal worth its salt, or any deal for that matter, will lay out in the fine print. The list of deliverables can stretch to nine pages long and will include things like:

E&O Insurance: Errors and Omissions Insurance. After I've proved that I did everything possible to mitigate possible lawsuits by having all those who appear in the documentary sign releases, making sure my music is legal, having no intentional slander and so forth, I still have to purchase an E&O policy in case something should arise down the road that could get me or the production company into legal hot water.

Music and FX. For global distribution, there may have to be some recutting, say, in Japan, to make the movie more palatable for a Japanese audience. Music, dialogue, sound FX: all these need to be delivered in a specific format so the editors over there can move things around, make changes, etc., to fit their audience.

Title Tracks. If the Slum Documentary gets shown in, say, Germany, all the subtitles, credits, even the Title, will have to be changed into the German language. There's a very specific way that all these titles have to be delivered to a third-party vendor to expedite that process.

There are a LOT more deliverables, but I'll just copy and paste a few from our notes so you get an idea of what goes on behind the scenes of every movie that actually makes it onto TV or the bigscreen or to your Netflix account:

(a) Original Picture Negative: The original first-class completely edited color 35 mm Film Stock Picture negative, fully timed and color corrected.

(b) Original Optical Soundtrack Negative: A first-class completely edited 35 MM Film Stock optical sound-track negative (including combined dialogue, sound effects and music made from the original magnetic print master described in Paragraph 5 below conforming to the original negative and answer print. The Sound track is to be in Stereo.

(c) 35mm Low Contrast Print: One (1) first class 35mm composite low contrast print fully timed and color corrected, manufactured from the original action negative and final sound track, fully titled, conformed and synchronized to the final edited version of the Picture(if available).

(d) Color Interpositive Protection Master: One (1) color corrected and complete interpositive Master of the Picture, conformed in all respects to the Answer Print for protection purposes without scratches or defects (if available).

(e) Color Internegative/Dupe Negative: One(1) 35 Internegative manufactured from the color interpositive protection Master conformed in all respects to the delivered and accepted Answer Print without scratches or defects (if available).

Get the idea? I'm becoming more and more convinced that trudging through the slums of the world is the easy part. The marketing and distribution is where it gets tough.

So that brings me back to Santa Monica. Our nine-week call sessions are ending with all of us here together at the Viceroy Hotel on the beach, discussing these issues, listening to experts in a variety of fields, and learning a lot. None of us want to join ranks with the countless filmmakers out there who have made a good movie, but then get hung up in this final stage of things.

Will this delay the release? Hopefully not … but better late than never.

Wednesday, April 8, 2009

Yes. It matters.

A boy is on the beach picking up fish, one at a time, and throwing then in the water.

A man tells the boy that he’s wasting his time, he can’t possibly save all the fish and it really doesn’t matter.

The boy stops and, looking at the fish in his hand, says, “it matters to this one.”

I’ve been rather astounded over the past few months as I’ve spoken to groups and individuals, of the number of people who are like that boy.

They hear the “one billion” but then they immediately want to know what they can do to help a person or a family. “How can we make a difference in the lives of the poorest of the poor?”

My own family is on an odyssey of sorts. Jovelyn is the 15-year-old daughter of Jose and Elvie Alquino, the family under the bridge in Manila. Jovelyn is a shy girl, bright-eyed and eager to learn.

Working with some very very fine people in Manila, we’re exploring the possibility of having Jovelyn come live with our family here in Iowa, finish her last year or two of high school in our small town, then go on to Dordt College where I teach.

It’s sort of like the kid on the beach. That kind of opportunity can matter—big time—to one family. And who knows what the ripple effect will be?

Many others want to know what they can do for the one billion.

I suspect there’s a way to create connections, but it needs to be done without reinventing programs and opportunities that other fine organizations are already involved with.

I’m delighted there are so many out there like that boy. I hope his attitude prevails, and that of the “it-really-doesn’t-matter guy” become a very small minority.

What's In A Name?

Not a real grabby title, is it.

Not like, “Warehousing the World’s Surplus Humanity,” or, “Zone of Silence” or a few other ideas I have for a title (in fairness, that first one about the “warehousing” comes straight from Planet of Slums by Mike Davis. I include it to make a point.)

So why the vanilla title?

As you may have read in a previous blog entry here, documentaries are definitely works in progress. They evolve. Heck, as of this writing, I’m still not 100% sure of the final direction this film is going to take. And I probably won’t know that ‘til I’m much further along in the shooting. To date, all I have is footage from Manila. Next month is Guatemala, and later this year, Africa. In between these will be interviews with a variety of experts.

As all this wonderful footage comes in, the ideas begin to gel, things come together, and yes, a title begins to emerge.

The title may come from something I read or a comment made during an interview. Some of the best titles come quite by accident in an off-handed remark made by someone, or the unusual juxtaposition of ideas when you see images cut together inside the Avid timeline.

What I’m saying is: “The Slum Documentary Film Project” isn’t the final title. It’s just a working title for a work in progress.

Eventually, something much better will reveal itself.

And then I’ll reveal it to you.

In the meantime, I’m wide open to ideas. If you suggest the title that ultimately gets used, be assured I’ll give you the credit when the credits roll on The Slum Documentary Film Project.

Tuesday, March 3, 2009

A Sense of Place

Friday, February 20, 2009

The Power of Media

Danny Boyle and his crew did an excellent job of capturing life in the slums of Mumbai. The grittiness of life there, and the desperation of slum dwellers is evident in many of the scenes in the movie.

Today, the news talks of some of the child actors from the movie who actually live in the slums. Azharuddin Mohammed Ismail, who plays the young Salim, elder brother of the film's central character Jamal, recently had his slum neighborhood razed and is now hoping for an actual house.

His father, Mohammed Ismail Mohammed Usman, who sells cardboard to eke out a living, said that since the movie came out, "The only thing that happened was that I became well-known because of my son. That's it. Nothing else changed. My kid became a hero and I'm living like a zero. This is my shack," he said.

The power of a film like “Slumdog Millionarie” is the power to get public attention focused on a subject like abject poverty. These people were acting, yes, but when the lights went off for the final time and the camera crew left, not much changed and the world is taking notice … at least of the few who appeared in the movie.

I really don’t think our documentary is going to sweep the world in quite the same way this movie did (but I can always hope). But our movie, like this one, will do its bit to help focus public attention on a subject that really needs the public’s attention. Mohammed, mentioned above, gathers up cardboard in hopes of getting enough money to live on. The Alquino family in Manila does that too. So do several families I shot in various parts of Nicaragua. As do people all over the world and yet the vast majority of these people will never be featured in a theatrical release or a documentary film. That doesn’t make them any less important. It just makes them less known.

Meanwhile, this very popular movie will eventually come out on DVD, then move to the “old” section of the neighborhood movie store. Eventually our documentary will come out, perhaps make a splash then also fade from the scene.

But the poverty won’t fade away, and if projections are correct, the one billion slum dwellers will grow to two billion and maybe more.

The power of media is to focus that spotlight. But that’s where it ends. To actually do something about it takes people who are committed to seeing real change.

Wednesday, January 7, 2009

It’s All About Improv

We wanted a shot that goes from the traffic on the top of the bridge, straight down to the ramshackle dwellings beneath the bridge.

We didn’t have a crane or a jib … or a helicopter, but we did have access to bamboo.

We asked a local under the bridge for a little help. He provided us with a rusty machete, a hammer of sorts, and two rusty nails that we straightened out. We used a long piece of bamboo laying near the canal and hacked off the end to make it flat. We pounded the two rusty nails in about three inches from the base of the pole. Then we put one of our came

ras upside down on the end of the pole and used gaffer’s tape to secure it tightly to the pole, using the nails to wrap the tape around (hard to explain, but it worked. The camera was very secure.)

ras upside down on the end of the pole and used gaffer’s tape to secure it tightly to the pole, using the nails to wrap the tape around (hard to explain, but it worked. The camera was very secure.)Then we had a dugout go in the canal beneath the bridge while we took our pole and camera up top. Making sure we watched for traffic, we lowered the camera—upside down—(we’ll fix it in post) near the water and slowly pulled the long pole and camera up topside. After about 10 tries, we felt we had a few good takes.

Watch for that shot in the final documentary. And do me a favor: Appreciate the sweat and improv that went into it!

Monday, January 5, 2009

"Poorism"

Mumbai, for example, has tours through the slums. Visitors come from around the world to gawk at the malnourished children and see the cardboard and iron-sheet structures that they call home. Some think this is a good form of responsible tourism as it exposes the more affluent to the reality of hundreds of millions of people worldwide. Others call it exploitation.

One person in India took this accusation of exploitation one step farther by saying,

"If you were living in Dharavi, in that slum, would you like a foreign tourist coming and walking all over you?" he sputtered. "This kind of slum tourism, it is a clear invasion of somebody's privacy....You are treating humans like animals."

A tourism official called the tour operators "parasites [who] need to be investigated and put behind bars," and a state lawmaker has threatened to shut them down.

Those are the thoughts I had in mind as all 10 of our students here in Manila accompanied our team of three into the garbage dump and slum in Cavite. We brought them in so they could experience first-hand what their teammates were filming, and to get a taste of what life is like in such a place.

Was this irresponsible “poorism”?

I sure hope not.

Did it feel weird to go in with 11 foreigners while dozens of Filipinos of all ages were scrambling … again… in the muck and garbage to

accrue the approximately $1 or $2 that most of them get by on a day? You bet it did. Ask any one of those students and they’ll tell you of feeling out of place, perhaps a bit exploitive.

accrue the approximately $1 or $2 that most of them get by on a day? You bet it did. Ask any one of those students and they’ll tell you of feeling out of place, perhaps a bit exploitive.At the same time, ask any one of those students if they have different thoughts now of what a slum is, of the reality of its awfulness, of the horrid, filthy conditions these people live in, and you might wonder if they’ll ever stop talking. These folks have now experienced firsthand what this stuff is all about.

I think there was a cost for us as Westerners to gain this empathy and understanding. The cost was some of the dignity of the people living in that slum. They knew what was going on. They knew rich people were coming to look at poor people. That’s a definite cost.

Was it worth it?

Time will tell. These students are on their way to becoming leaders in many different arenas of life. This experience won’t leave them. Perhaps they won’t leave the experience. Perhaps one, or two, or all of them, will use their considerable gifts and talents in the years to come to make a difference.

In my mind, that’s different than “poorism.” That’s tourism with a purpose.

Saturday, January 3, 2009

Under the Bridge

hour that rumble across one of those nondescript bridges over just one more canal in this archipelago nation.

hour that rumble across one of those nondescript bridges over just one more canal in this archipelago nation.But this bridge is more than just a bridge. Underneath it is an entire community. Just below the rumble of traffic is a group of people eking out a living in the nearby Las Piñas dump.

For me, the “one billion” slum dwellers of our world now have a face, thanks to that bridge community. In fact, faces. An entire family. Spending time this week with this family is helping me move past the statistic and into the realization that each and every digit in that “one billion” has hopes and aspirations, dreams and wishes. I heard them today in our interview with the Alquino family beneath the bridge.

We (Piper Kucera, Peter Hessels and I) first met Jose Alquino Jr. and his wife, Elvie, in the dump in Santa Cruz, a small town in the Pulon Lupa Barangay in Las Piñas City. They and three of their six children were huddled down in garbag

e. Literally. Trucks from the city come in, disgorge their fetid contents and the residents of the dump swarm over it with short, curved metal hooks to help them get at the recyclables as quickly as they can. The Alquino’s 12-year-old son, Arnel, is the best at this as he’s small and quick. Jose and Elvie, with Jovelyn, their 15-year-old daughter, then sort through the garbage looking for plastic, aluminum, tin and best of all, copper. They, and dozens of other people from this community, spend their days sifting through other people’s garbage, trying to make a living.

e. Literally. Trucks from the city come in, disgorge their fetid contents and the residents of the dump swarm over it with short, curved metal hooks to help them get at the recyclables as quickly as they can. The Alquino’s 12-year-old son, Arnel, is the best at this as he’s small and quick. Jose and Elvie, with Jovelyn, their 15-year-old daughter, then sort through the garbage looking for plastic, aluminum, tin and best of all, copper. They, and dozens of other people from this community, spend their days sifting through other people’s garbage, trying to make a living.Jose says on a good day, the family can make about 200 pesos. At an exchange rate today of about 47 pesos for one dollar, that’s about $4.25 a day. Jovelyn is the only one of the six children in school because they can’t afford to send any more.

Elvie also sells fish in a market further north. She gets up at 3 a.m. to buy the fish near the sea where they live, then travels by bus and jeepney to a different market to sell.

These are hard working people. Uneducated, but desperate to see their children do better than themselves. We interviewed them and asked questions about their lives. They were open and honest and cheerful … mostly. Jovelyn cried—though she tried desperately not to—as she told us about going to school hungry. Elvie cried—before quickly bouncing back to her more exuberant self—as she talked about having one meal a day, usually. She said she wants her children to have a better life than she does, but it’s so hard.

Meanwhile, the traffic continues to pound the pavement just a few feet above our heads, and the KLM jets continue to roar overhead because this slum is directly under the flight path for the Manila International Airport.

We left at the end of the day to drive back into the center of Manila. As we left the slum and maneuvered our way back to the main roads, we finally got onto the highway and went North. As we did, we rumbled over a bridge. And I looked back and realized we had just rolled over—literally—Jose and Elvie’s bedroom.

And I almost didn’t notice.