In Guatemala, that’s not so unusual. Last year, 620 women were murdered, and not one person was brought to justice over it.

While filming in Guatemala, we are staying at a seminary, the largest in Latin America. It’s a beautiful oasis in a violent city. High walls

surround lovely green areas, well-manicured lawns, well-kept buildings and engaging students.

surround lovely green areas, well-manicured lawns, well-kept buildings and engaging students. We left the compound at 8 a.m. for our day of shooting. At 7:30 a.m., the woman who cleans the rooms, makes sure the towels are fresh and who keeps the guest comfortable, was dropped off right in front of the main gate of the seminary.

A student who lives across the street was an eye witness to what happened next.

The cleaning woman (who’s name I do not know) alighted from the vehicle and moved toward the gate.

A car sped around the corner and a well-trained assassin leaned out the window with his pistol and shot the woman in the head.

The eye witness said it was a well-executed operation by a well-trained person. Apparently it’s quite easy to hire such a person in Guatemala.

One of the seminary professors knew the woman quite well and she’s the one who told us about the 620 murders of the previous year. Trembling with anger and frustration, the professor told us that most likely, some routine paper work would be done on this murder and then it would be put in a file somewhere and would most likely never see the light of day again.

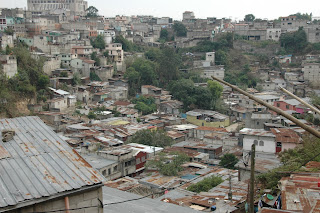

Seeing her anger and helpless frustration gave me an inkling of what the residents of La Limonada slum must feel at times. The Ministry of Justice building is an imposing structure (see photo) that stands literally on top of the ridge

overlooking La Limonada. The task of the Ministry of Justice would be similar to the FBI in the USA. They are charged with investigating murders, suspicious deaths, etc. Being so close to La Limonada, a violent slum in a violent city, should be job security for them.

overlooking La Limonada. The task of the Ministry of Justice would be similar to the FBI in the USA. They are charged with investigating murders, suspicious deaths, etc. Being so close to La Limonada, a violent slum in a violent city, should be job security for them.However, as we found out, what happens in La Limonada stays in La Limonada. According to those who live and work down in that deep ravine, murders that happen there are just not worth investigating by the Ministry of Justice.

At certain times of the day, the shadow of the Ministry building literally falls into the slum. But that’s about all the residents of the slum will get. Murders down there are not investigated.

Imagine being one of those residents and knowing that murderers can operate with impunity. Simply being a resident of La Limonada makes you unworthy of official protection. You’re on your own.

The United Nations says some characteristics of slums include lack of security of tenure, lack of security and lack of sanitation. For those in La Limonada, we could also add lack of rights.

own words, she went from a hard gang member, to a women with a deep faith in God, despite a personal story even the best Hollywood writers would have a hard time matching.

own words, she went from a hard gang member, to a women with a deep faith in God, despite a personal story even the best Hollywood writers would have a hard time matching.